What Changed My Mind About Depression? Not Medication—But This Daily Practice

Depression isn’t just sadness—it’s a slow fog that dulls everything. For years, I thought it was something I had to live with, until I realized small daily shifts could make a real difference. This isn’t about quick fixes or miracle cures. It’s about practical, science-backed habits that help prevent depressive spirals before they start. If you’ve ever felt stuck in the same loop, this might be the perspective shift you’ve been waiting for.

The Hidden Trigger: Understanding the Modern Roots of Depression

Depression is often misunderstood as prolonged sadness, but its true nature runs deeper. It manifests as cognitive fog, where even simple decisions feel overwhelming. Energy drains from the body like water through a cracked vessel, and emotional numbness replaces once-vivid feelings. This condition does not always stem from trauma or loss—modern living itself has become a silent contributor. The routines many consider normal, such as irregular sleep, constant digital stimulation, and social disconnection, quietly erode mental resilience over time.

Research increasingly shows that lifestyle factors play a significant role in the development and persistence of depressive symptoms. Chronic sleep disruption interferes with brain chemistry, particularly the regulation of neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine. Digital overload, especially from social media and late-night screen use, heightens mental fatigue and reduces attention span. Meanwhile, rising levels of social isolation—despite being more “connected” than ever—deprive individuals of meaningful emotional support. These conditions do not necessarily create clinical depression overnight, but they lay the groundwork for emotional instability.

It is important to distinguish between clinical depression and situational emotional fatigue. Clinical depression is a diagnosable mental health disorder that often requires medical intervention, including therapy or medication. Situational fatigue, on the other hand, arises from prolonged stress, poor self-care, or environmental strain. While less severe, it can mimic depressive symptoms and, if unaddressed, may evolve into a more persistent condition. Recognizing this difference allows individuals to respond appropriately—whether through self-management or professional support.

Prevention, rather than crisis response, should be the priority. Consider the case of a woman in her early 40s, juggling work, family, and household responsibilities. She feels persistently tired, irritable, and disconnected. She assumes her state is normal for someone in her position. Yet, her symptoms reflect a pattern of gradual depletion. By adjusting daily habits—such as prioritizing rest, reducing screen time, and scheduling moments of stillness—she begins to regain clarity. This example illustrates how early intervention through lifestyle changes can halt the progression toward deeper emotional distress.

Why Traditional Advice Falls Short: The Gap in Mental Health Guidance

Well-meaning advice like “just go for a walk” or “try to stay positive” is common, yet often unhelpful for those experiencing low mood. Such suggestions assume that motivation is readily available, which is rarely the case when depression takes hold. When energy and focus are diminished, even small tasks require extraordinary effort. Telling someone to “snap out of it” ignores the biological and psychological barriers they face. This gap in mental health guidance leaves many feeling misunderstood and defeated, as if their struggles are a personal failure rather than a complex interplay of factors.

The flaw in motivation-based strategies lies in their timing. They ask individuals to act when their capacity to act is lowest. Neuroscience shows that in states of low mood, the prefrontal cortex—the brain region responsible for decision-making and planning—functions less efficiently. Expecting someone to generate willpower from this state is like asking a car with an empty tank to drive uphill. What is needed instead is a shift from motivation to action, where behavior precedes feeling. This is the foundation of a therapeutic approach known as behavioral activation.

Behavioral activation works on the principle that action can lead to emotional change, not the other way around. By engaging in small, structured activities—even when motivation is absent—individuals begin to rebuild a sense of agency. For example, a person might commit to sitting by the window for five minutes each morning with a cup of tea. This act requires minimal effort but introduces a moment of consistency and calm. Over time, such actions accumulate, creating a momentum that supports improved mood and energy.

A real-life example illustrates this shift. A woman in her 50s, recovering from a period of prolonged low mood, started with a single daily task: opening the curtains upon waking. This small act exposed her to natural light, regulated her circadian rhythm, and signaled to her brain that the day had begun. Gradually, she added a short walk, then a five-minute journal entry. These actions were not driven by enthusiasm but by commitment to the routine. Within weeks, she noticed subtle improvements—more energy, better sleep, and a slight lift in mood. Her experience underscores that change does not require grand gestures but consistent, manageable steps.

The Power of Micro-Habits: How Tiny Changes Rewire Your Brain

The brain is not fixed; it adapts based on repeated experiences—a concept known as neuroplasticity. This means that daily behaviors, no matter how small, can reshape neural pathways over time. When it comes to mood regulation, consistency matters more than intensity. Micro-habits—tiny, repeatable actions—serve as gentle but powerful tools for rewiring the brain’s response to stress and low mood. Unlike drastic lifestyle changes that often fail due to their demands on willpower, micro-habits are sustainable because they require minimal effort and decision-making.

Three science-supported micro-habits stand out for their impact on mental well-being: morning light exposure, intentional movement, and structured routines. Morning light exposure helps regulate the body’s internal clock, or circadian rhythm, which influences sleep, hormone release, and mood. Just 10 to 15 minutes of natural light shortly after waking can signal the brain to reduce melatonin production and increase alertness. This simple act has been linked to lower rates of seasonal affective disorder and improved emotional stability throughout the day.

Intentional movement, even in small doses, activates the body’s natural mood-enhancing systems. Physical activity increases blood flow to the brain and stimulates the release of endorphins and dopamine—neurochemicals associated with pleasure and motivation. The key is not vigorous exercise but consistent motion. A two-minute stretch upon waking, a brief walk around the block, or standing while making a phone call can all contribute to this effect. These actions break the inertia of stillness, which often accompanies low mood, and create a subtle but meaningful shift in energy.

Structured routines provide the brain with predictability, reducing the cognitive load of constant decision-making. When life feels chaotic, a simple schedule—such as waking at the same time each day, eating meals at regular intervals, or setting a consistent bedtime—offers a sense of stability. This predictability calms the nervous system and reduces anxiety. Over time, these routines become automatic, requiring less mental effort and creating a foundation for emotional resilience. The power of micro-habits lies not in their size but in their repetition, which gradually reshapes the brain’s default state toward greater balance.

Your Environment Shapes Your Mind: Designing a Depression-Resistant Lifestyle

The spaces we inhabit and the sensory inputs we encounter daily have a profound influence on mental state. A cluttered, dimly lit room can amplify feelings of stagnation, while a well-organized, naturally lit space can promote clarity and calm. The nervous system responds continuously to environmental cues—light, sound, temperature, and even scent. When these inputs are chaotic or overstimulating, the brain remains in a state of low-grade stress, making it harder to recover from emotional dips. By intentionally shaping the environment, individuals can create conditions that support mental stability rather than undermine it.

One of the most impactful changes involves managing light exposure. Bright, artificial light in the evening—especially from screens—suppresses melatonin and delays sleep onset. In contrast, exposure to natural daylight during the day strengthens circadian rhythms and improves sleep quality. Simple adjustments, such as using warm-toned lighting at night, turning off digital devices an hour before bed, and opening curtains in the morning, can significantly enhance mood regulation. These changes do not require major renovations but consistent, mindful choices.

Creating calming zones within the home can also serve as emotional anchors. A designated chair near a window, a small reading nook, or a corner with plants and soft lighting can become a retreat for moments of stillness. These spaces do not need to be large or elaborate; their value lies in their consistency and intentionality. When a person knows they have a place to pause and reset, they are more likely to do so, breaking the cycle of constant doing and mental overload.

Social and digital environments also require thoughtful design. Constant notifications, endless scrolling, and comparison-driven content on social media can heighten feelings of inadequacy and isolation. Setting boundaries—such as designating screen-free times, muting non-essential alerts, and scheduling low-pressure social interactions—can reduce mental clutter. For example, a weekly phone call with a trusted friend, free from agenda or performance, can provide connection without stress. These environmental tweaks do not eliminate challenges, but they create a buffer against the daily pressures that contribute to emotional fatigue.

Food, Gut, and Mood: The Silent Connection Most People Ignore

Emerging research highlights a powerful link between the gut and the brain, known as the gut-brain axis. This bidirectional communication system means that digestive health directly influences emotional well-being. The gut houses trillions of microbes that produce neurotransmitters, including about 90% of the body’s serotonin—a key chemical involved in mood regulation. When the gut microbiome is imbalanced, due to poor diet, stress, or antibiotic use, it can contribute to inflammation and mood disturbances, including symptoms of depression.

Diet plays a central role in maintaining this delicate balance. Highly processed foods, excessive sugar, and trans fats promote inflammation and disrupt microbial diversity. In contrast, whole foods—such as vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds—provide fiber and nutrients that feed beneficial gut bacteria. These foods also stabilize blood sugar, preventing the energy crashes that can worsen mood swings. Hydration is equally important; even mild dehydration can impair concentration and increase feelings of fatigue.

It is not necessary to follow a restrictive or trendy diet to support mental health. Sustainable patterns matter more than perfection. A simple approach includes filling half the plate with vegetables at meals, choosing whole grains over refined ones, and incorporating plant-based proteins. Fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, and sauerkraut may also support gut health, though individual tolerance varies. The goal is not rapid transformation but gradual, consistent nourishment that supports both body and mind.

Studies have found that dietary patterns rich in whole foods—such as the Mediterranean diet—are associated with a lower risk of depression. While diet alone cannot cure clinical depression, it can serve as a foundational support. For many, improving nutrition leads to increased energy, better digestion, and a subtle but noticeable improvement in mood. This connection reminds us that mental health is not isolated to the brain but is influenced by the entire body’s condition.

Sleep as Prevention: Why Rest Is the Foundation of Mental Resilience

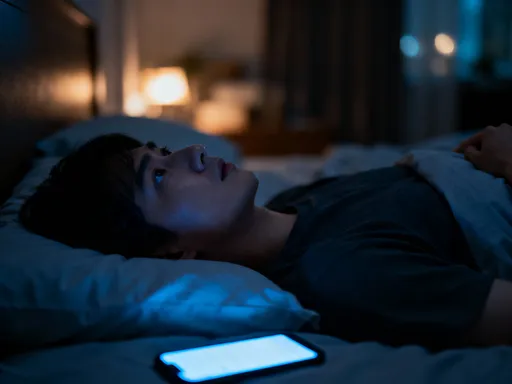

Sleep is not merely a passive state; it is an active process essential for emotional regulation and cognitive function. Poor sleep disrupts the brain’s ability to manage stress, increases emotional reactivity, and impairs memory and decision-making. In the early stages of low mood, sleep disturbances—such as difficulty falling asleep, waking frequently, or ruminating at night—are often among the first signs. These disruptions create a vicious cycle: poor sleep worsens mood, and low mood further degrades sleep quality.

Rumination, the repetitive looping of negative thoughts, is particularly common in the quiet hours before sleep. Without effective wind-down strategies, the mind remains in a state of hyperarousal, making rest elusive. This is where non-medical interventions can make a significant difference. Establishing a consistent bedtime routine signals to the body that it is time to transition into rest. This routine might include dimming lights, reading a book, practicing gentle stretching, or writing down thoughts in a journal to clear the mind.

Light management is another critical factor. Exposure to blue light from screens in the evening suppresses melatonin, the hormone that regulates sleep. Avoiding screens for at least an hour before bed—or using blue light filters—can improve sleep onset and quality. Additionally, keeping the bedroom cool, dark, and quiet creates an environment conducive to deep rest. While sleep duration is important, sleep quality is equally, if not more, vital. Fragmented or shallow sleep does not provide the restorative benefits the brain needs.

Consistency matters more than perfection. Going to bed and waking up at roughly the same time each day—even on weekends—strengthens the body’s internal clock. This regularity reduces the mental effort required to fall asleep and wake up, making rest more accessible. For those struggling with insomnia, the goal is not to force sleep but to create conditions that invite it. Over time, these practices build a foundation of mental resilience, reducing vulnerability to prolonged low moods.

When to Seek Help: Recognizing the Line Between Self-Care and Professional Support

Self-care practices are powerful tools for maintaining mental well-being, but they are not a substitute for professional treatment when needed. There is no shame in seeking help; in fact, it is a sign of strength and self-awareness. Therapy, counseling, and medical evaluation provide essential support for those experiencing clinical depression or persistent emotional distress. Normalizing these resources helps dismantle the stigma that often prevents individuals from reaching out.

Red flags indicating the need for professional support include persistent feelings of hopelessness, inability to function in daily life, loss of interest in all activities, significant changes in appetite or weight, and thoughts of self-harm. If low mood lasts for more than two weeks or interferes with work, relationships, or self-care, it is important to consult a healthcare provider. Early intervention can prevent symptoms from worsening and support faster recovery.

Prevention and treatment are not opposing paths—they are complementary. Daily habits such as good sleep, nutrition, and routine can reduce the risk of depression, but they do not replace the need for therapy or medication in more severe cases. Think of mental health like physical health: regular exercise and a balanced diet support heart health, but they do not replace medical treatment for heart disease. Similarly, self-care strengthens resilience, but professional care addresses underlying conditions.

Proactive check-ins with a doctor or therapist should be part of routine mental hygiene, just like annual physicals or dental cleanings. These visits allow for early detection of changes and provide a space to discuss concerns before they escalate. By integrating self-care with professional support, individuals create a comprehensive approach to mental well-being—one that honors both personal effort and the value of expert guidance.

Preventing depression isn’t about eliminating sadness—it’s about building a life that supports mental clarity and emotional balance. By focusing on daily habits, environment, and early awareness, we can reduce the risk of falling into prolonged low moods. This isn’t a cure, but a commitment to self-awareness and care. Small choices, made consistently, can become the foundation of lasting mental well-being.